There is a subdivision near my daughter’s school called ”Travis Country.” We pass by the limestone sign every day, surrounded by verbenas and turk’s caps, shining brightly in the sun.

“Who’s Travis?” she asked one morning. “And why did they name this place after him?” Despite my various inadequacies, I felt relatively comfortable explaining who this person was that so important to our state’s history. After all – I was born and raised in Texas. I grew up forty-five minutes from the Alamo. If anyone could tell her who Travis was, I could. Here was my very helpful answer:

I think he was a Colonel in the Republic who fought at the Alamo. Did he wear a coonskin cap? No, wait. That was Davy Crocket. Anywho, it was either he or some other dude that met with a Mexican leader under a tree regarding surrender. No wait, that can’t be right. Well I don’t know his first name, honey. But I think his middle name started with a B.

Yes, folks. That’s it. Colonel Travis wore a coonskin cap while not dying at one of the biggest battles in Texas history because he apparently morphed his ghost-like dead self into Sam Houston and was busy negotiating a surrender. Most importantly, however, his middle name started with a B. Of that, I’m certain. Well thanks a lot, small-town history teacher. Thanks a lot.

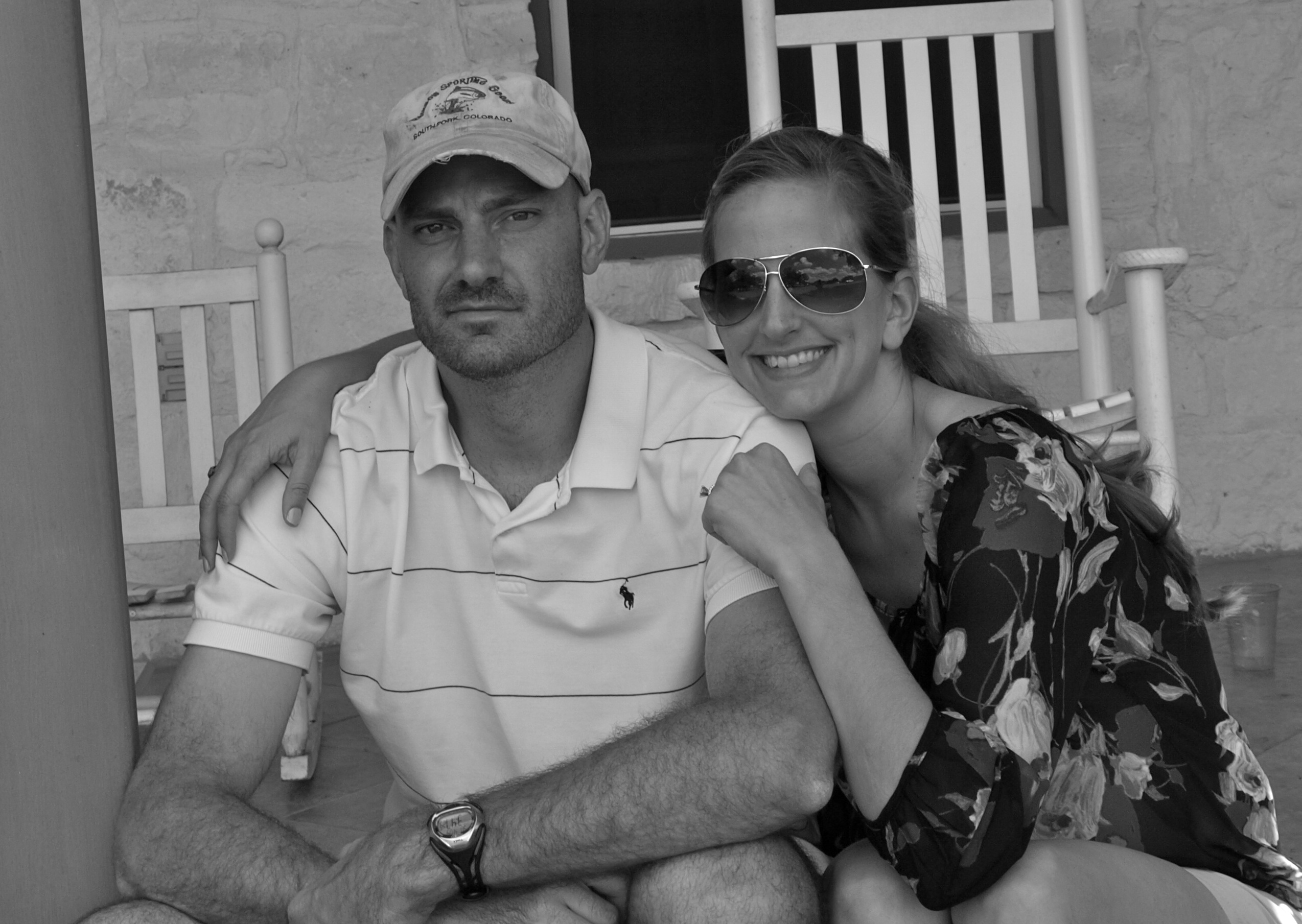

That night, I asked my husband to better explain it. His first response was “please tell me you didn’t try.” What? Why would he jump to such accusatory conclusions? I lied and said no, even though I’m very well-versed on the subject and all. He snickered at that. So at bedtime, my husband allowed my daughter to stay up late in order to re-tell the story of William Barret Travis dying in a hard-fought battle against Mexican soldiers, leading a team of outnumbered and starving misfit settlers. He dramatically drew his hand across the bedcovers to imitate how Lt. Col. Travis drew a line in the sand, urging those who wouldn’t fight-to-the-death to walk away. No one walked. They all crossed that line. My daughter sat up with rapt attention. Please don’t mention the coonskin cap, I thought as I tried to beam it directly into my daughter’s head. I’ll never live that one down.

The way my husband wove the tale you’d think it was a work of fiction, with William Travis walking away from a sordid past in Tennessee to find his home in this rugged new place, leading a pack of dirty men, all huddled behind a Catholic mission’s dirt-and-mortar walls. They all died bloody deaths in the battle of the Alamo, but the Mexican soldiers finally prevailed. “A woman named Susana Dickenson survived to tell the tale,” my husband said with raised eyebrows. My daughter breathed in fast. What did she do? Where did she run? Why did they let her go? The stinging smell of independence hung like fog in the air around her pink covers. The Battle of San Jacinto. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. The capture and surrender. Gunsmoke.

I passed the sign again today and it had new significance. It reminded me of why I live in the great state of Texas, tucked away in the hill country amidst bluebonnets and wild Indian blankets, the soil fertilized with the blood of those who died for our right to stake a home onto this great land. The tall, blowing grasses are moistened by their tears, and their yet untold lives whisper to me in the afternoon winds. This state is special not just because of the stories told today, but of stories long since past.

On February 24, 1836, mere days before the end, Travis wrote to the people of Texas and all Americans in the world, saying “I am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna. I have sustained continual bombardment and for twenty-four hours and have not lost a man. . . I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, and our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of liberty, of patriotism and everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch. The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily and will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor and that of his country. Victory or death.”

Thank you, William Barret Travis. For the fight. For the intensity for which you loved this place. For drawing that line in the sand. I thank God for you, for what you did for us so many years ago, and for your unyielding urge to never give up even as solders were climbing the wall and closing in. I salute you, my dear patriot. Even if it makes people look at me funny while I drive by that sign, in my sweats, possibly talking on my cell phone, on a Tuesday afternoon.

Others might have chosen to walk away – but you? In that dark day in March, 1836, as you breathed your last breath, you thought not of these things. You thought of victory.